a short history of Dutch Carp Farming

BY KASPER ZOM

It was an early morning in June 1980 at a small farm pond deep in a valley in Herefordshire, when Dave Short snapped some pictures on his Minolta camera of a fish so big, it would prove a British record. The fish was a carp of more than 51lbs. It was caught by Chris Yates, originally from Burgh Heath, Surrey. The location was the almost mythical Redmire Pool. Like that other famous fish, Clarissa, caught by Dick Walker from the same pool, it is a quintessential moment in carp fishing history.

Let us follow in the ‘footsteps’ of fifty tiny Dutch carp destined for greatness. Our voyage starts at the birthplace of The Bishop and Clarissa, as I visit the small village of Vaassen in the Netherlands and will inevitably end at that famous pool near Llangarron. We will investigate the onset and consequences of the Agricultural and Industrial Revolutions in the Netherlands and the UK, the profound effects of the Great Depression on international trade, the social-cultural history of fish farming and water management in the Netherlands… and how one thing led to another!

Present Day: Vaassen

The sun was bright and the sky a deep blue when I arrived at my destination. I parked the car, and walked a few yards along a road aptly called Fish Farm Road before coming to what seemed to be the edge of a dense forest, but which on inspection turned out to be a completely overgrown pool.

Overgrown growth pool

I had stumbled upon one of the growth pools of the former fish farm in Vaassen, now overgrown with reeds and lilies, the sides dotted with bushes, herbs and small trees. Further along, the wall of small trees at the side of the pool opened and the true scale of the water was revealed. The surface of the pool was almost completely covered in lilies, their white flowers opened wide towards the sun. Any part of the water that wasn’t covered by lily leaves had either reeds or water plants in it. A choir of birds sang from the trees; I could hear a chaffinch, great tit and blue tit. A buzzard was shrieking overhead but because of the thick canopy, I had no chance to spot the bird myself. I came towards the corner of the rectangular pond and turned right to keep following it. This seemed to have been some kind of farm entrance in the past because there was a large spacing between one pond and the next one, leaving room for a path that led deeper into what looked like a forest. Except it wasn’t; at every turn there was another view of a pond, a small vista through the trees of another derelict pool that was once the centre of activity for tens of employees and thousands of fish. After another left turn I found myself on a twelve foot wide dyke between two overgrown pools. The pool on the right no longer had any water in it but was now filled with trees and shrubs. Long-tailed tits were searching for food in a birch tree, hanging upside down seemingly without any effort. In the distance I saw a flash of bright blue and orange along the broad path. A kingfisher had been startled by my arrival and disappeared up a tree as I paused at the corner of two large dykes. The presence of humans was still visible and with some imagination, it was possible to envisage farm staff netting the pools while walking along the dykes. Fifty years later, nature had almost completely taken over.

Growth pond with lilies and reeds

Growth pond with open water and lilies in the distanced with lilies and reeds

Small dike between two ponds, completely overgrown

View of the corner of a former pool with one of the larger dikes, capable of accommodating a horse drawn cart

There was one specific location I wanted to find. To get there I had to retrace my steps through the maze of dykes and former ponds, back to Fish Farm Road. I walked north, crossed the outlet of a stream and walked across a field towards a wall of reeds. It was difficult to recognise it from the historical maps, since the shape and size of the ponds had completely changed due to sand extraction in the 1970s. But this was still the place, the birthplace of The Bishop. The water was crystal clear, the bottom a sandy light brown and the lake was surrounded by mature trees and bushes. This truly was the place where history was made. But how did it start here, and more importantly, why?

Former location of the spawn and stretch ponds

Revolutions

This history doesn’t commence in 1980, nor in 1934 when the small carp were originally stocked in Redmire Pool by the equally famous Donald F. Leney, co-owner of Surrey Trout Farm. It doesn’t start at Redmire, nor in that small Dutch village of Vaassen. The foundations of these events were laid at a much earlier time, roughly around the mid 1700s in Great Britain and greater Europe. The Agricultural Revolution was a period of unprecedented growth, caused by several events, small revolutions following each other. These encompassed a new system of crop rotation to turnips and clover (for fixing minerals and nitrogen), the introduction of the Dutch plough (a Chinese design from the Han dynasty), introductions of new crops such as the potato, and the expansions of roads and inland waterways. In the 19th century, another innovation would be added to the mix; one that would have far-reaching consequences for this story. Newly discovered fertilisers meant large quantities of nitrogen, phosphate and potassium could be added to soil in the form of sodium nitrate, seabird guano or potash. The increase in agricultural production was so great, and the labour needed declined so drastically, that the Agricultural Revolution is said to have caused that other great revolution, the First Industrial Revolution . Finally, an urban workforce was at hand to kickstart industrialisation. It led to a period of massive economic growth that was, as is never the case, not without an end. In 1873, the world plunged into the Long Depression and with it came an agricultural crisis, caused by a market flooded with US and Canadian products. The agricultural workforce went through hardship in Western Europe, and in the Netherlands by the end of the 1800s, action was needed.

Heidemaatschappij: Dutch fish farming near Vaassen

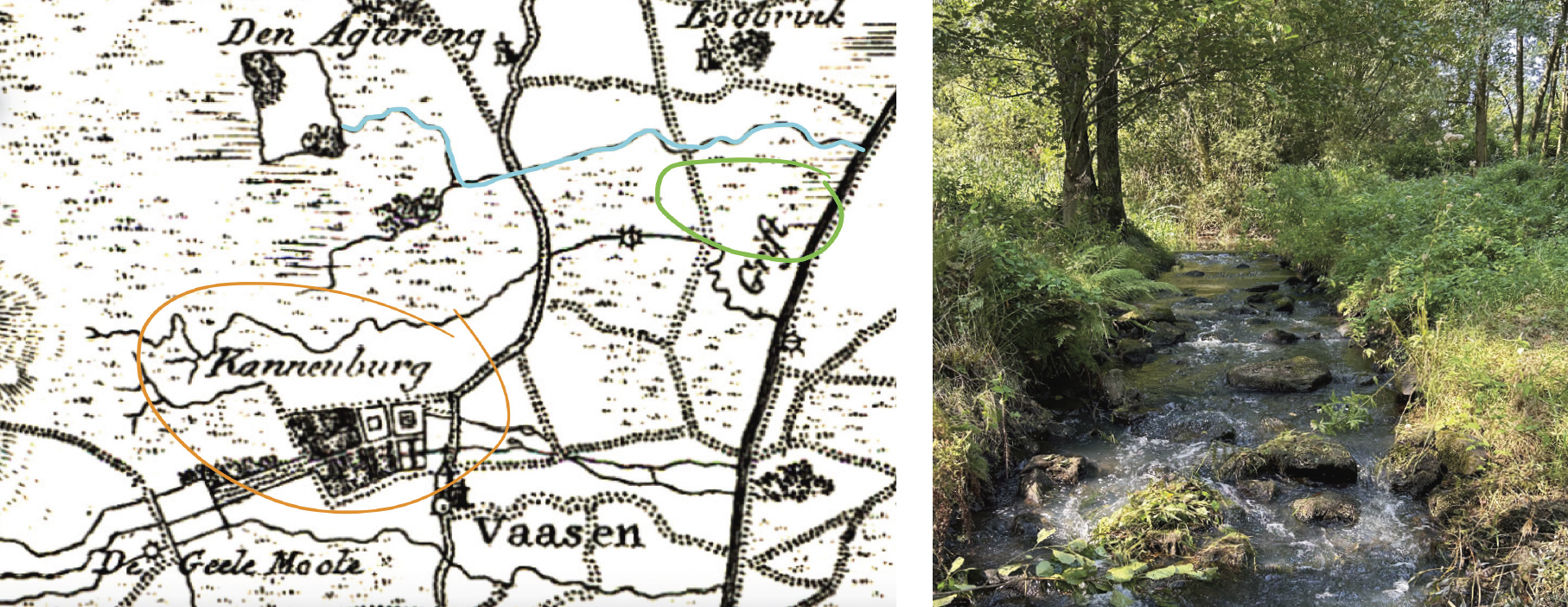

The ‘Nederlandsche Heidemaatschappij’, the Dutch Moorland Reclamation Society, was founded on January fifth 1888 as the result of a law change in 1886 that allowed the owners of communal “wastelands” to develop these grounds for agriculture or forestry and create employment for farmers and other workers. Dutch heathland in the east of the country mainly consisted of sand dunes and bushes, and the ecological value was ill-understood. In 1898 the Heidemaatschappij started the Department of Freshwater Fishing. Initially, ornamental ponds were used in the gardens of Castle Cannenburgh near Vaassen, which was built on the ruins of a much earlier, medieval structure. However, since the moats and ponds of the castle were limited in size, in 1899 a much larger fish farm was constructed a few miles northeast of the castle.

The choice for this particular location is fascinating, since it has been a centre of economic activity for centuries. This part of the Netherlands is known for the natural rise and fall of the land, and the existence of many natural streams. One of the main streams around Vaassen is the Smallertse Beek (‘beek’ is Dutch for ‘stream’). Known as a seepage stream, water naturally comes up from the ground because of groundwater pressure and follows its course to lower ground. For centuries this was mainly used to power water mills, and several paper and copper mills have existed in this area. The power of water was so important that another stream, the “Handelse Beek”, was “beheaded”, meaning its flow was changed right at the source of the stream, so it could augment the flow of the Smallertse Beek to power watermills. With the advent of the steam engine (yes, revolutions will keep influencing this history) the importance of water mills decreased, and the area needed a new form of economic activity.

Enter the Heidemaatschappij, which was looking for an area with clean, oxygen-rich streams and enough natural fall to repeatedly empty and fill up fishponds. The Smallertse Beek had slightly warmer water because of its long run above ground from its source (although at the source water from seepage streams is typically a very constant eight degrees Celsius throughout the year) and was therefore used to fill a series of spawning and stretching ponds, used for spawning and initial growth of the young carp.

With the watermills gone, the Handelse Beek no longer needed to deliver water to the Smallertse Beek. Its course was changed again, and it was fed through an underground system of pipes under the railway track. Now it delivered fresh, very cold water year-round to the larger growing ponds, where two or three year old fish could be grown. The farm was positioned between the railway in the west and a large shipping channel in the east. The location was ideal both for growing the fish and for the logistics of transporting them.

Historic map from the 1920’s, showing the Smallertse Beek (blue), Handelse Beek (green), the location of the former watermills (magenta cross) and the site of the brick factory neighbouring the fish farm (yellow circle).

The spawning ponds were typically thirty by sixty feet and only twelve inches deep. They were only filled with water during spawning season, when the parent animals were let loose in the shallow ponds to spawn and lay their eggs in the tall, underwater grass. The ponds were temporarily emptied to remove the parent animals and refilled with water to allow the young carp to hatch and grow. After a few days they would start feeding by themselves and after a few weeks they were transferred to the stretching ponds for further growth. The growth ponds, used for two and three year old fish were larger, typically an acre in size and much deeper.

The Heidemaatschappij used techniques discovered during the Agricultural Revolution.To promote the health of the soil, ponds were left dry some years and crops were grown on the, now green, fields. Fertiliser was used

to improve the soil during the year the ground was left bare; after tests with guano and manure, the company settled for compost. The increase in insect life in the grounds fed a next generation of carp when the ponds were flooded once more. The incredible results of these techniques were discovered haphazardly at Redmire, when the pool almost dried up in the summer of 1976. The increase of biodiversity in the pool after it refilled with water was such that it allowed Chris Yates’ record fish, The Bishop, to grow from 33 to its eventual 51lbs.

Pest control was an issue at the fish farm during the first years and animal welfare was not top-of-mind in the early 1900s. When frogs were found to eat young carp en-masse, they were caught, killed and boiled, only to be ground and mixed with flour to feed the young fish. Birds received a similar ‘welcome’ when they were found to prey on young carp; hundreds were killed each year, among them herons, seagulls and kingfishers. Still, the freshwater fishing endeavour was a great economic success in the early 1900s.

This cannot be said of other companies in the area. In 1898, the same year that fish farming started in Vaassen, Mr Vlasveld, the owner of a papermill in the area purchased 16 acres of land just south of the land that would eventually become the fish farm. In 1906, he sold it to an entrepreneur wanting to start a brick factory. The sand needed for the bricks was dug up from their own terrain to the northwest, thereby creating the future growth ponds of the fish farm. The company went bankrupt, restarted in 1912, but had to finally cease production in 1917 when due to the Great War demand for bricks nearly disappeared. At the end of 1917, the plant manufactured carton but in 1926, environmental issues developed. At this time, the Heidemaatschappij had expanded and was now using the ponds dug out years before by the former brick factory.

They needed clean and oxygen-rich water, and the neighbouring carton factory was a problem. In his report, municipal overseer Mr. Bontekoe mentions that “wastewater is streaming from the factory into the nearby stream (…). The water is red and mixed with fine paper fibers (…) undergoing a process of rotting”. When the Labor Inspection came to call on the company on February tenth 1927, the place was deserted. It would not be the last time that water pollution featured prominently in this story.

Donald Frank Leney

A few years before Mr. Bontekoe wrote his damning environmental report, the neighbouring fish farm had been visited by Donald Frank Leney, who in a large part shaped modern carp fishing as we know it today. As the co-owner of the Surrey Trout Farm, he established a long and fruitful relationship with the people of the Vaassen fish farm that lasted for decades, surviving both the Great Depression and the Second World War.

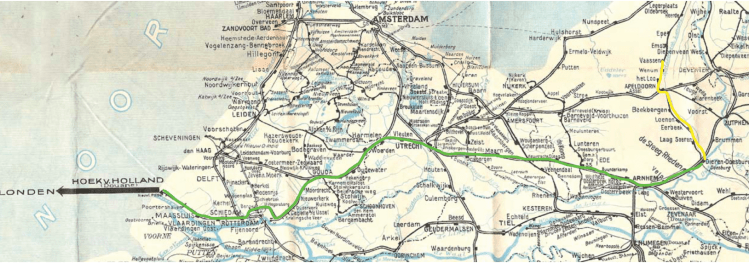

Born in 1901 in a family of brewers, Leney chose his own path and quickly showed his passion for fauna when studying at New College, Oxford under Julian Huxley. In one of his many papers regarding experiments on amphibian metamorphosis, Huxley mentions that “acknowledgement is made to Mr D.F. Leney for assisting in the care of the animals”. Apart from an interest in nature, Leney had a keen business instinct and in 1923 became a shareholder at the Surrey Trout Farm & United Fisheries Ltd. By 1925 he had established contact with the fish farm in Vaassen, helped by the advent of a regular steamboat service between Hook of Holland and Harwich (revolutions, again!). The Heidemaatschappij was happy to accommodate their international customers and prices for carp and other fish included delivery to Hook of Holland by rail.

Economic Turmoil: Great Depression

From 1925 onwards, Leney visited the farm in Vaassen every year at the end of autumn and brought back barrels full of tiny carp. Business for the Surrey Trout Farm was strong, in part because of an established network of patrons in the UK among Dukes, Earls and Viscounts. But for most people around the world however, dark clouds were gathering. On October twenty-ninth, 1929, stock prices on Wall Street collapsed and it started a period of worldwide depression. The Roaring Twenties had seemed a time of unlimited growth and expansion, which now came to a sudden and painful halt. The Great Depression lasted until 1939 and fuelled unhappiness among citizens in such an extreme way, it is seen as one of the major reasons the Nazi party was able to attain power in Germany in 1933.

The consequences of that for our story wouldn’t become clear until later in the decade. For Leney, in1933, the thought of war was still far away, and he travelled to Vaassen again late autumn for his annual purchase of carp. Prices of carp had been coming down dramatically since the beginning of the Great Depression.

Between 1924 and 1929, the price of 3-4” yearling carp had come down by roughly 30% and until 1936 it would go down another 25%.

In 1933, demand for carp was so low, that the entire production of the sister facility of the Vaassen farm in Valkenswaard had to be sold to buyers abroad for half the catalogue price (which was already significantly down from the beginning of the decade). Foreign shipments always went through the Vaassen site, and it is very likely that Leney also bought part of the Valkenswaard stock, but what is certain is that in 1933, prices were at an all-time low. Leney left for Hook of Holland with barrels full of small fish. Between them were fifty 5 ½ – 8 inch carp that would be destined for Redmire Pool. This included The Bishop and Clarissa, the two most famous English Carp in history, fish that would inspire generations of anglers and kickstart a carp fishing industry worth millions of pounds. But in 1933, these tiny fish were bought at an absolute bargain.

Destination: Redmire

The little carp were not going to Redmire Pool to become legends. Stories of monster carp were still twenty years away at that point. Lt. Col. Barnardiston, the owner of Bernithan Court Farm, needed a way to control the growth of weed in his farm pool. The water was used to supply the estate with water via an innovative pumping system, but the extensive weed was clogging it up. As mentioned before, Surrey Trout Farm had excellent connections and on March tenth 1934, fifty small carp were plunged into the pool, supposedly to eat the weed. Why was there a weed problem? To answer, we need to look at the main reasons for weed growth in lakes and ponds, namely nutrient levels, light penetration, water movement and the introduction of non-native species. The latter three may have contributed but were likely not the main reason. However, Bernithan Court was – and is – surrounded by farmland. Therefore, the most logical explanation for the extensive weed growth in the pool in the 1900s is the level of nutrients introduced by agriculture surrounding the pool.

To back up my claim, I turned to the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology and the University of Lancaster, who in 2021 published a paper on “Long term simulations of macronutrients (C, N and P) in UK freshwaters”1. Their extensive modelling points to pollution by agriculture and sewage as the main contributors of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus to freshwaters, rising from the beginning of the 1900’s until finally decreasing in the 2000s. Although these generic models are made to explain levels across the entire country and local nutrient levels might not perfectly fit the models, the timeline matches exactly what happened at Redmire Pool in the early 1900s and explains why action was needed in 1934. The reason the Dutch carp existed in the first place and the reason they were eventually stocked into Redmire Pool are two sides of the same coin: both are directly caused by the events set in motion by the aforementioned Revolutions, especially by the introduction of fertiliser and the increased productivity that it created. Cause and effect in its ultimate form.

1 “Long term simulations of macronutrients (C, N and P) in UK freshwaters”, V.A. Bell, P.S. Naden, E. Tipping et al, 1 March 2021

The Trip of a Young Carp

Leney was not the first to bring carp across the English Channel from the Netherlands. The first time the event was recorded was in 1626, when Pieter de Latfeur, a rich merchant from Amsterdam, sent eight carp over to Ireland to stock the fishponds of the Great Earl of Cork at Lismore Castle. Three hundred years later, it was Leney’s turn. In the 1930s, travel by train was well established in both the Netherlands and Great Britain and daily steamboats sailed from the harbour of Hook of Holland directly to Harwich. From there, it was onwards by train and flatbed truck to Haslemere, or even further to the Surrey Trout Farm location at Nailsworth.

Historic 1930’s map of train routes in the Netherlands, showing the local train from Vaassen to Dieren (yellow) and the fast train route from Dieren to Hook of Holland (green)

In the Netherlands, the journey started at the Vaassen train station, where a local freight train brought the cargo to the station at Dieren. In the early years there were many problems with logistics and fish often had to wait for hours at the Dieren station for connection to fast trains. By 1933 however, most problems had been worked out, and the trip was smooth. From Dieren, a fast train connection took a westerly course through the country to the port of Hook of Holland. The train passed cities such as Utrecht, Gouda and Rotterdam but before that, it passed a city called Arnhem.

Had Leney looked out the left window at Arnhem (and maybe he did), he would have seen a bridge crossing the Rhine River. He couldn’t know that ten years later, his fellow countrymen would be fighting and dying on that same bridge to force a quick attack route into Germany 2. Nor did he realise he would be part of that army…

2 Operation Market Garden, Sept 1944

Second World War

During the Second World War, trade with the UK came to a halt as the Netherlands was occupied by forces from the Third Reich. The Dutch government capitulated after Rotterdam was bombed on May fourteenth 1940. During the war, production at the fish farm became increasingly difficult. Food for the small fish was hard to get and the lack of fertiliser greatly damaged the production numbers. The focus shifted from providing fish for inland fish stocks to securing food for an increasingly famished population. The German occupiers even resorted to grenade fishing to empty ponds for food.

Leney in the meantime, had other things to worry about. After the British Expeditionary Force was evacuated from Dunkirk in June 1940, Leney was awarded an emergency promotion to Lieutenant and joined the Royal Corps of Engineers. By now he had fifteen years of experience in the transportation of cargo from Europe to the UK and this had not gone unnoticed; he joined the Transportations Service within the Corps. He quickly moved up the ranks and was a Captain by February 1942. On January eighth 1943, he was given a position within the War Office, Department of the Quarter-Master-General to the Forces, as a Staff Captain under the Director of Transportation, Maj.-Gen. D.J. McMullen. Among other tasks, the Transportation Service, which grew from just four thousand troops before the war to one hundred and forty-six thousand personnel, oversaw the construction of railways, harbours and other vital infrastructure to support the war. They were responsible for the famous Mulberry Harbour during the Normandy Campaign and supported the war all the way through Belgium, The Netherlands and Germany. Leney left the army after the war ended and retired as a full Major. He returned to civil life and the Surrey Trout Farm.

Post-War years and Decline of the Vaassen farm

After the war, fish farming by Heidemaatschappij saw some recovery, but the decline that started in the 1930’s was irreversible. In 1971 the department of Freshwater Fishing ceased to exist and the land close to Vaassen was returned to nature. But not entirely… in the 1970s large amounts of sand were needed for the construction of a highway from nearby Apeldoorn to Zwolle. Again the “wasteland” near Vaassen had to deliver its resources to support economic growth. The former spawning and growth ponds were dug out further to form one large lake. Today the lake is used for recreational purposes such as surfing, swimming and boating, its old function no longer visible in the landscape. A 1991 ecological study of the entire area confirmed its great value for nature: aside from an impressive number of aquatic plants and other herbs, shrubs and trees, the area is home to a large variety of birds, five distinct types of bats and twenty-six species of butterfly. A fitting purpose for an area that has been so resourceful to humans for nearly four centuries.

Leney continued his successful enterprise after the war. Using his knowledge and network he helped introduce American Char to high altitude artificial lakes in Kenya when the people there found it was too cold for trout or tilapia to spawn. He also aided Dr. Hamilton at the Naturalist’s Department in Stanley, Falkland Islands with the introduction of Brown Trout and arranged for the transport of ten thousand eggs. For the remainder of his life, he lived at the beautiful Springhead house in Haslemere, Surrey, until he passed away on October thirteenth 1987, at the age of eighty-six. It marked the end of an era of carp history. As for me, I still had one last stop to make on my own historical journey…

Present Day: Redmire

After a car ride through the sloping, green June countryside, I arrived at an entrance gate with a white sign on the side that simply read “Bernithan Court Farm”. I drove over the cattle grid and could see the estate house in the distance upon the hill. Further down to my right was a lane that ended at a black fence. Through the fence, the road led slightly down into the valley towards the car park near the pool. It’s here that I was met by Les Bamford who has taken care of running the fishery for many years. Redmire has undergone a complete restoration at the hands of Mark Walsingham to bring the pool back to its original state as it was in the 1950s when it was first fished; silt that had accumulated throughout the decades has been removed and otter fences have been put in place to prevent predation; a common problem at carp lakes throughout the country nowadays. The landscape around the pool has also been adapted in such a way that runoff from nearby farmland is caught before reaching the water, hopefully preventing the lake from silting up again.

After a chat with Les and his bailiff, I decided on a stroll around the water, starting at the location where Yates once landed his record, at the top of the pool. The day was slightly overcast, and it had rained during the night. My right boot sank away in mud with a colour of bright, rusted iron; red mire! Reaching the top of the pool I looked down into the shallows. The inlet stream was bubbling in the background and the undergrowth there was plentiful. I was now at the exact location of that famous moment in fishing, some forty-four years ago, but the pool remained silent. This was the place; this was the end of my journey, this was the site I had read so much about. The water was a pale emerald colour and gin clear, the bottom visible for several feet out. There was no wind, and not a single ripple on the surface. Apart from a small family of ducks swimming at the dam, the lake was eerily quiet, for now anyway.

From the top of the pool, I decided to walk around to the other side via the dam. This is easily the most recognisable part of the lake. I passed the overspill, where water leaves the lake and plunges down into the lower lake. The depth is a few inches here, before dropping down along the dam. A long, narrow patch of weed was visible along the middle of the water, where the deeper channel is. Other than that, the weed growth near the edges seemed very limited. There was not a carp in sight, although there was a watery sun behind the overcast skies and the air was warm and humid. The ducks near the dam wall looked at me anxiously – not fond of anglers most likely – and quickly swam towards the shallows. A wren flew low over the dam and disappeared in the green overhanging the outlet stream. I made my way to the Willow Pitch. Diagonally opposite from the place where Yates caught the Bishop, this is where that other famous Redmire carp, Clarissa, was landed by Richard Walker. The willows aren’t there anymore, but the place still provides the angler with that magical overview of both dam and water. I made my way further up the west bank, past the punt, Stile and Kefford’s pitch, towards the islands.

There on the west bank, near the islands, is another significant place. In October 1981, about eighteen months after Yates’ record capture, angler Barry Mills noticed a carp floating on the surface. It turned out to be the Bishop. He retrieved the fish from the water and placed it in a small grave on the west bank under an elder.

I now realised I had come full circle, from the place of birth of that famous fish to its final resting place. And as if to underline my sudden realisation, it finally happened…

The family of ducks, thinking themselves safe in the shallows, had been eyeing my every move suspiciously as I came up the west bank and decided it’d been enough. As one they took off under a loud quacking and winged along the length of the pool. Passing very low over the lake’s surface, they inadvertently startled some other, previously unseen inhabitants, hiding in between the weeds. As if orchestrated, the pool came alive and a dozen carp simultaneously dove for the safety of the channel depths, whacking their strong tail and leaving behind vortices on the water surface. As quickly as it happened, the water was back to its former, tranquil state. But Redmire had finally given me a hint of its underwater magic, the historic pool had spoken….